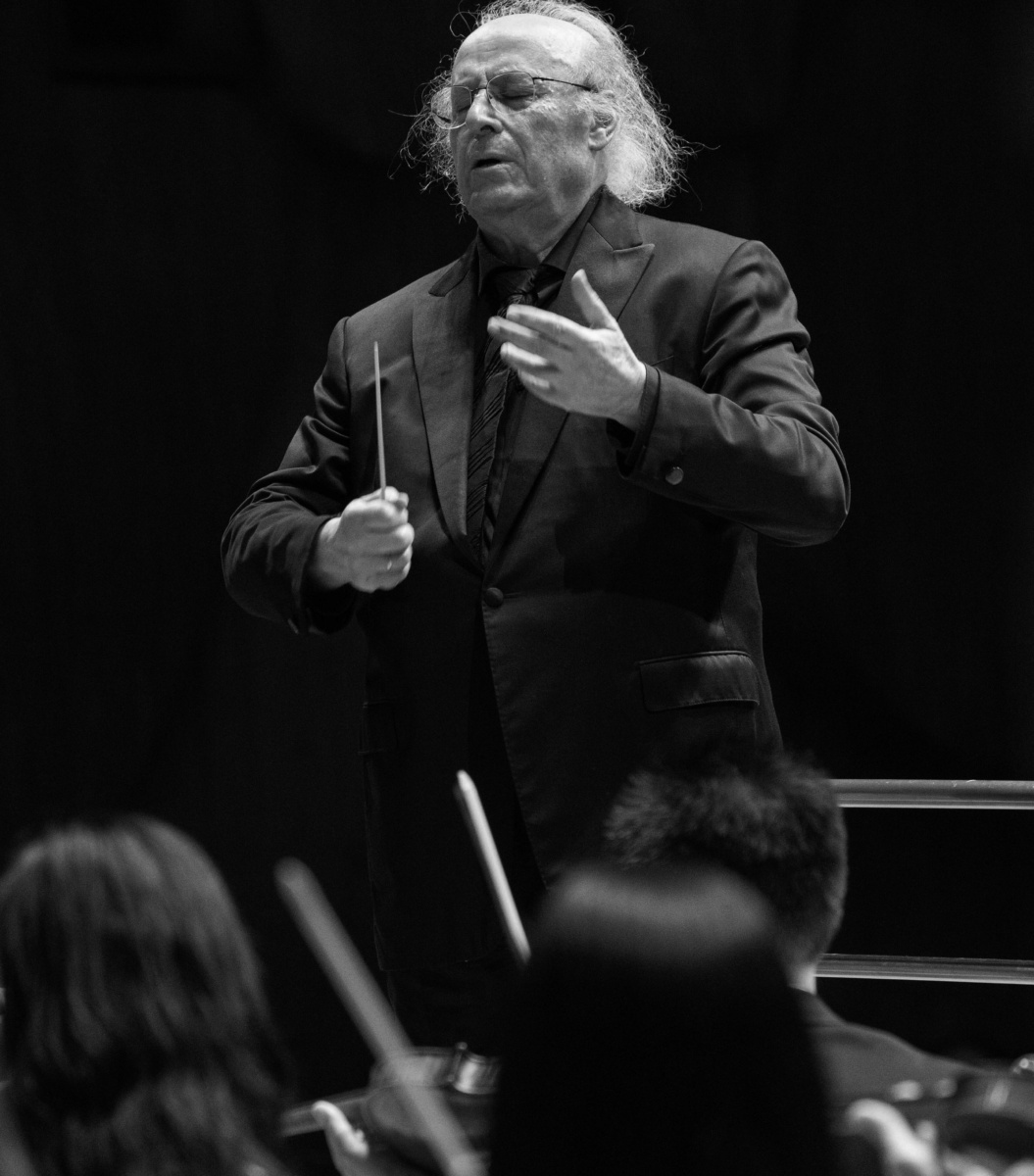

Eliahu Inbal celebrates his 85th birthday on 16 February, 2021. We say "happy birthday" - and again present our three-part series of interviews with the conductor, first published in 2016.

Alongside numerous other vinyl and CD productions, the Bruckner cycle with the Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra (hr-Sinfonieorchester), then the Radio-Sinfonie-Orchester Frankfurt, was the one that really brought you into the public eye and is still considered legendary. How did your relationship with the orchestra begin?

I came upon an orchestra that had lots of opportunities but also lots of problems. Generally the attitude was that the orchestra wasn’t meant to play in the premier league – and I wanted to go straight into the premier league! I had to change a lot of things and unfortunately that meant making some painful cuts. Back then I was very enthusiastic and thought that the orchestra wasn’t doing anything – no records, no tour – and that just wouldn’t do. I started with recordings. The large cycles that we recorded were very important for the orchestra because they were appreciated by international audiences.

How did this opportunity come about?

When I was still with Philips I made recordings with the London Philharmonic and Claudio Arrau, which were very successful. With Bruckner I was the first person to conduct the original versions of the third, fourth and eighth symphonies, which no one wanted to play because they are so difficult. Teldec was keen to record them and this resulted in a complete recording. Many other projects followed including the cycles by Dvořák and Stravinsky. Denon became aware of me because I always conducted a Mahler symphony to great acclaim when I went to Japan. They then released the Mahler cycle with the RSO Frankfurt. I think it was the first digital complete recording and thousands of copies were sold. Later on I also recorded the cycles by Berlioz and Shostakovich, Schumann, Webern and Brahms with Denon. All of that, first the vinyl records and then the CDs, put my name on the map as it were. And it has stayed there ever since.

When a conductor arrives with a recording team and is able to make such great recordings happen, this must also have an effect on his relationship with the orchestra.

Yes, of course. The orchestra developed enormously, as did the tours that we went on with this repertoire. A provincial atmosphere surrounded the orchestra when I first encountered it, and I changed this. When I left the Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra it was internationally famous and it still enjoys this level of prestige today.

The recordings also promoted you as a conductor.

Without a doubt. I would put it like this: when a conductor comes to an orchestra there are two situations. Either he is unknown and it all depends on how he presents himself in the first few minutes; or he arrives with a history, he has a name, then he automatically enjoys more authority. I profit enormously from the latter. Some also possess natural authority or charisma but the fact that I was particularly well-known as an interpreter of Mahler and Bruckner thanks to the recordings was doubtless an advantage.

Your work with the Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra was far from your only long-term post as chief conductor. What is it like for you now when you guest conduct these orchestras with which you have such a close connection?

When I return to an orchestra, which I have worked with for many years the sound changes the moment I stand in front of the musicians. They know what I wanted back then – this happens with La Fenice, the Konzerthausorchester Berlin, in Frankfurt, with the Tokyo Metropolitan, Czech Philharmonic. It’s as if I have returned to my family. This contact remains. And the phrase “Inbal sound” is used.

These orchestras differ greatly regarding their individual sound. Do you have an “Inbal-Konzerthausorchester-sound” in your head and an “Inbal-Fenice-sound” or do you wish to achieve the same sound with every orchestra?

That is an interesting aspect because every orchestra has its own quirks. And then I come along with my vision. There is an “Inbal sound”. But it cannot be the same with every orchestra; I would never want to take the Japanese part out of Tokyo for example. I would like to keep the qualities, features and characteristics of each orchestra and profit from them – and on top of that achieve my “Inbal sound”, and of course my interpretation.

How do you develop your interpretation – how do you find your key to a work?

There are things that are easy to understand: analysing the score, the structure, is the same for all conductors. But then the spiritual and emotional content needs to be taken into consideration. The meaning of the music: what story is it telling, what does it want to imply. This is when the person Inbal comes into play and I have to be in harmony with the score. Let’s take Bruckner’s Symphony No. 4 as an example. I have conducted it many times but now I take another look at the score and explore what it is saying to me and what that means to me. New aspects emerge each time because times change, I change, the world faces different problems. This is all reflected in the music. And of course there is no right or wrong. It’s individual and that’s what makes the interpretation. Another conductor will discover something else in the music. And that’s fine, otherwise it would be boring.

We’ve also spoken indirectly about where you have lived – today you live in Paris. That does not seem like an obvious choice: your wife is German, your children partly grew up in Germany.

That may be due to sentimentality. One’s student years are very important, very formative – romance and of course the material itself that you studied combine. The desire to live in Paris again someday was always very strong. I lived in Germany for a long time until 1990 and after that considered moving back to Israel but my wife didn’t want to. And so we returned to Paris.

You are conducting a lot of concerts around your birthday. Are you fulfilling yourself with them?

I am happy with my current experiences. Getting to know new orchestras and returning to many I already know well gives me great pleasure. All that I now wish for is quite banal: health and a long life so that I can see my children – and grandchildren – for a long time to come.

We wish you that too from the bottom of our hearts!

Nina Rohlfs 01/2016 | Translation: Celia Wynne Willson