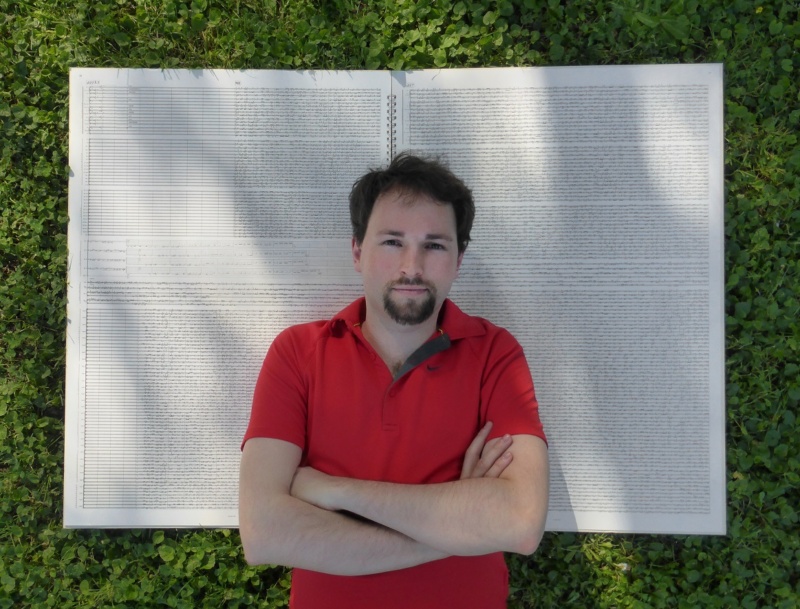

It is 8 December 2018, and the first world premiere in eight years at the Vienna State Opera creates great attention in the press. The Austrian composer Johannes Maria Staud (born 1974) and the Dresden-born poet Durs Grünbein (born 1962) have created a politically-charged opera which warns of a Europe drifting to the right. The duo, who have already worked together on two operas and a monodrama, searched for “contemporary material that shows the insecurity of society,” and were inspired by the works of Joseph Conrad, H.P. Lovecraft, Algernon Blackwood and T.S. Eliot.

The libretto and score for Die Weiden were written in parallel, developed through constant communication. The story, rich in metaphor, is built around a young couple’s journey down a river. Peter (Tomasz Konieczny), an artist, wants to show the philosopher Lea (Rachel Frenkel) his home. For her, this expedition is also a search for traces of her family history, as her ancestors were displaced from this region. Whilst at first the pair enjoy the bliss of love, this is increasingly disturbed by threatening forms seen in the landscape. Nightmarish encounters tip the story into the surreal and hallucinatory. Carp-like creatures appear; beings who were once human and are now just part of the masses, robbed of their own opinions and power to decide for themselves. In Andrea Moses’ production, people increasingly take on the characteristics of carp, with impressive face masks – as fascinating as they are repellent – bringing this process to life before our eyes.

This metamorphosis is echoed in the music, with the singer’s voices coloured with water sounds. For this, Johannes Maria Staud masterfully uses live electronic techniques: “those are phenomena such as Granular Synthesis, Convolution or Resonance Filtering. The voices receive a tail, somewhat noisy, that unfurls electronically.” The great river flowing through Europe separates and comes together again and forms the basis of the opera’s shimmering tone colours – as well as its central motif. “That was about generating the sound of water without working with actual recordings of water,” explains the composer. The opera is divided into six scenes, four passages, a prologue, overture and an interlude; its vocal writing demands a whole spectrum of singing styles from the performers; and an actor playing a composer and actress playing a TV reporter move the action along. The four instrumental passages are each based on a solo instrument, around which live electronics are built. The tuba, contrabass clarinet, double bass and bassoon are submerged in the orchestral sound which plays with various water associations, made apparent through video projections of stormy river landscapes and willow branches swaying in the wind.

The astonishingly large-scale ensemble, including choir, orchestra (with a vast percussion section), tape and live electronics, 18 singing and speaking roles – many of which are minor roles – creates a panopticon rich in variety. Powerful orchestral passages are placed alongside spoken passages; musical borrowings from light music accompanying a dance troupe are heard next to intimate electronic sounds in which one can almost hear mosquitoes in the meadows. Johannes Maria Staud already worked with this juxtaposition of contradictory material in his 2017 orchestral work Stromab. The diversity of the music is also echoed in the various levels of the libretto, as well as the love story and Lea’s confrontation with her own family history, which comes to a head in an imagined meeting with the victims of the death marches of Hungarian Jewish forced labourers in 1945. There is the constant threat to civil society posed by the darkness and populism through demagogues who aim to manipulate the masses.

The connection between plot and music is made explicit in the opera, not least through the figure of the composer (Udo Samel), tellingly named Krachmeyer: “the composer cannot sing, but rather speaks of the sound of home and of cultural purity – things that, for me, do not work, but I would gladly discuss with him. For me, he is an unlikeable but simultaneously highly enticing and manipulative figure.”

At this opera house, rich in tradition, conductor Ingo Metzmacher succeeds in leading the Orchestra of the Vienna State Opera in a multi-faceted performance rich in variety that arises from the tension between “lyrical introspection and dramatic intensity.” (Staud)

Marie-Therese Rudolph (for our print magazine, published in spring 2019)

Translation: Samuel Johnstone

Additional performance dates at Wiener Staatsoper: 7, 9 and 12/11/2019