I have known Friedrich Cerha since the mid-1980s. It was probably HK Gruber that introduced him to the Ensemble Modern, which I was managing at the time. In his works Keintate I + II and Eine Art Chansons he wrote a chansonnier part that was particularly suited to Nali Gruber, and which he still often performs. We soon invited Friedrich Cerha as a conductor and made guest appearances with him including at the 1988 Salzburg Festival. In the 1990s at the Vienna Konzerthaus I got to know the composer even better, and we regularly programmed works of his, both small- and large-scale. I have particularly vivid memories of the performances of his Langegger Nachtmusik III and a Webern programme he led with the Klangforum Wien.

We started working for Friedrich Cerha in 2005, and his 80th birthday was celebrated a year later with several concerts. I expected that we would mostly be concerned with promoting the existing oeuvre of this extraordinarily productive composer. Within Austria he was celebrated as its leading composer, but he had a much lower profile elsewhere. I was therefore all the more surprised that in the following ten years, he produced over 50 large- and small-scale works for orchestra, every one of them a masterpiece, and mostly compiled into cycles: Momente (world premiere: BR Symphony Orchestra 2006), Berceuse celeste (Stuttgart Radio

Symphony 2007), Instants (WDR Symphony Orchestra 2009), Kammermusik für Orchester (Vienna Musikverein 2010), Like a Tragicomedy (BBC Philharmonic 2010), Tagebuch für Orchester (HR Frankfurt 2014), Drei Orchesterstücke (WDR Symphony Orchestra 2014), Nacht (Donaueschingen 2014), Bagatelle (Bamberg 2016), Elf Skizzen für Orchester (Konzerthaus Berlin 2016), Drei Sätze für Orchester (Vienna Musikverein 2016), Eine Blassblaue Vision für Orchester (Salzburg Festival 2016), Drei Situationen für Streichorchester (Wien Modern 2018), as well as the Violin Concerto for Ernst Kovacic (Vienna Konzerthaus 2005), Aderngeflecht for Baritone and Orchestra (with Georg Nigl, Steirischer Herbst Graz 2007), the Clarinet Concerto for Andreas Schablas (2008), the Percussion Concerto for Martin Grubinger (Salzburg 2009), the ‘musical farce‘ Onkel Präsident (Prinzregenttheater Munich 2013) and a large number of chamber and ensemble works.

Working for Friedrich Cerha proved profoundly different than working for any other composer. Normally our work consists of finding commissions, negotiating them, completing the contracts and working them into our composers’ schedules. But with Friedrich Cerha it is exactly the opposite. His composing schedule – as much as there is one – is as far as I can tell unknown to all, not revealed to anyone, not even his wife. Friedrich Cerha’s creativity is completely independent from receiving commissions – he composes, inspired by his reflections on music, by encounters with friends, musicians and other artists, and by art and literature. On some pieces he works for years, whereas others come to him in a dream and have to be written down that night. When a work is completed, he tells his wife, who delivers the happy news to us, often with the title and the precise timing. We then only have to take care of the commission and the world premiere, which in most cases only takes place years later.

It was only a couple of years ago that I first visited the Cerhas at their summer house in Langegg where they generally spend the summer months, a quiet, isolated place with views over a tranquil hilly landscape, and really started to appreciate how Friedrich Cerha can be so productive. Shortly before I was due to leave, returning to my children in Vienna, Mrs. Cerha said to her husband: “Now you have to show him your pictures.” I had once seen a couple of his works in a gallery in Graz and knew about of his passion for painting. But I was all the more surprised when we climbed up two flights of stairs to find the entire attic completely filled with paintings of various sizes. Fascinated, I looked at a few of them, but accepted that there were many large groups of works which I couldn’t possibly appreciate in a single evening. I cannot judge the value of the art, but the mastery with which various materials were used in pictures that could almost be seen as sculptures was striking. Clearly, this is abstract art that is nevertheless inspired by concrete objects; timeless art that arises from a very personal connection to the respective material.

“You paint just as much as you compose,” I realised, completely taken aback. “Yes, I mostly work on three pictures simultaneously – two always have to dry before starting work on them again.” “And you’ve been doing this for decades – how many exhibitions have you given?” “One of them you saw, in Graz. There was also a group show in Salzburg.” “And that’s it?” I haven’t been able to forget the answer he gave me: “If no one had promoted my compositions, then it would have been exactly the same for my music.”

Translation: Samuel Johnstone

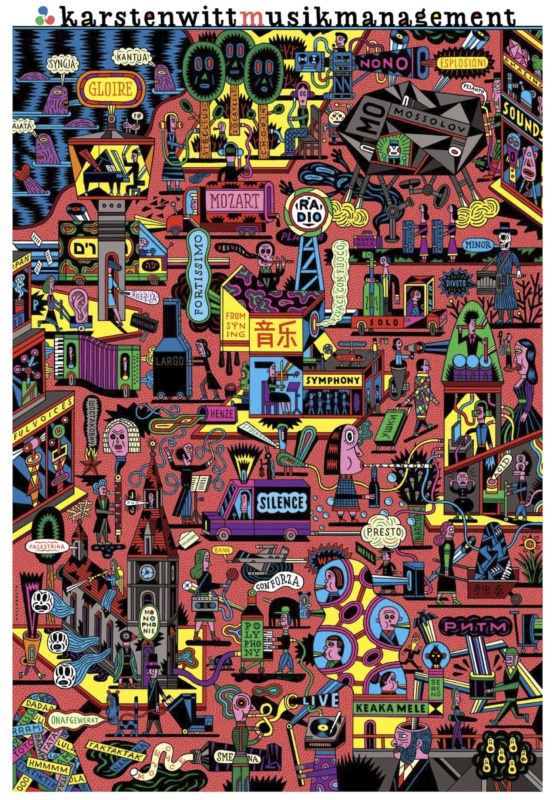

The text first appeared in 2015 in the anniversary magazine on the occasion of the 15th anniversary of Karsten Witt Musik Management.