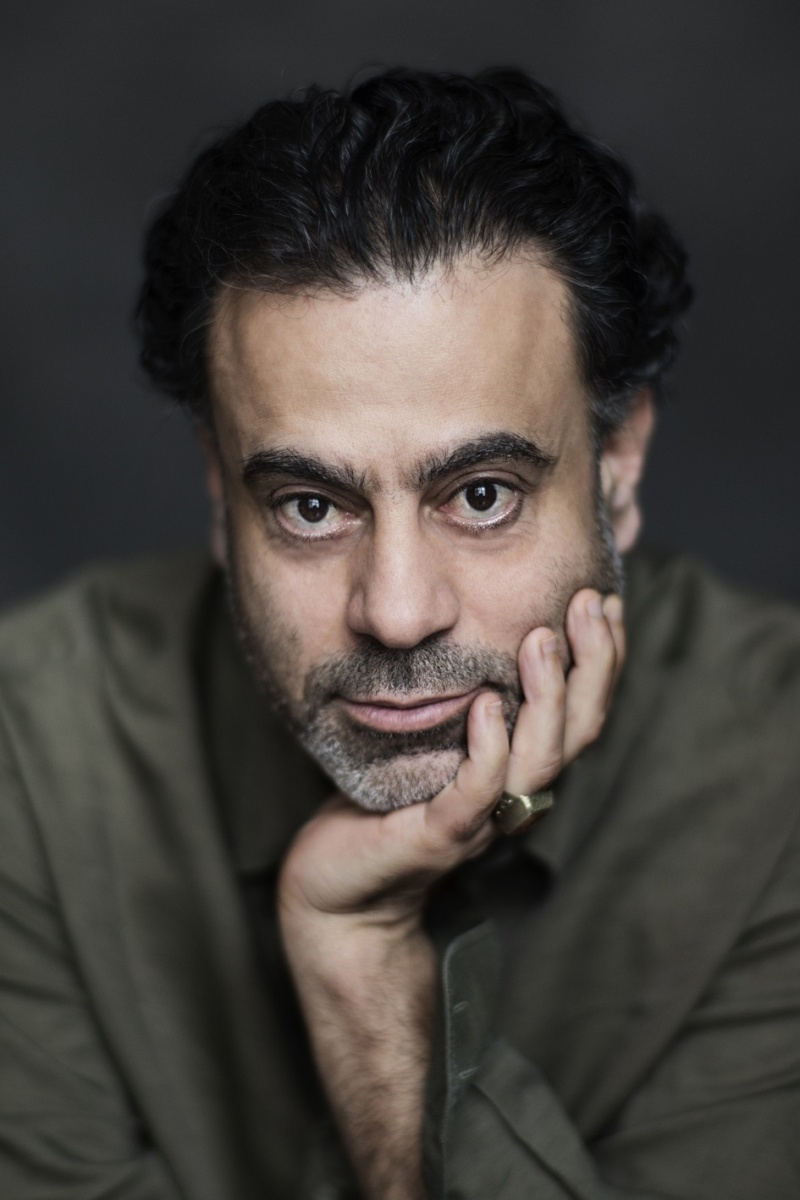

Samir Odeh-Tamimi’s Mansūr for large choir, four brass players and two percussionists received its world premiere 2014 at the Salzburg Festival with great success. The work, which was commissioned by the Festival, is based on texts by and reflections on the Sufi mystic Mansūr Al-Hallāğ (858-922), with which the composer has dealt with in several of his works already. This article originally appeared in the Salzburg Festival programme booklet for the world premiere.

Mansūr begins with low drum beats, hardly audible, sounding

from behind the audience, appearing out of nowhere besides the rhythmic

singing of a few singers. Upon closer inspection, the whole piece

reveals itself during this simple start: Samir Odeh-Tamimi has split the

text between four choir groups. These, as well as the instrumentalists,

are positioned around the audience in the room. The composer does not

distribute the different registers and instruments symmetrically but

lets them form triangles with voices and instruments throughout the

whole room. When the trombones and percussion then combine with these

tones, the acoustic space extends right out into the whole church. He

pitches individual notes extremely high or low in order to enlarge this

space and envelop the audience in piano and pianissimo notes or

captivate them with mezzo forte or fortes.

The first low notes played by the instruments lay the foundations for the basic element of the piece, the text from the The Garden of Knowledge by Mansūr Al-Hallāğ. He is quoted straight away in the first few bars: "she is not him and he is not her, and only she is him and only he is her." The explosive power of the mystic Mansūr Al-Hallāğ’s message can already be gleaned in these verses, which still seem confusing at first glance. He invited his followers not to look for new definitions for and images of Allah. According to Mansūr Al-Hallāğ you will only find true knowledge within yourself. For Samir Odeh-Tamimi, these are the central verses, so dense and meaningful in terms of content that he practically lets them ring out on their own.

The Sufi rhythm in which Mansūr Al-Hallāğ wrote these verses becomes the rhythmic foundation for the music. Even if Samir Odeh-Tamimi says that he is not a religious man and that he did not write this work for religious reasons, this Sufi rhythm does mean a lot to him musically speaking. The dance-like triple rhythm, with a spring in its step, a rhythm which has a light movement to it, has been with him since childhood. It is a rhythm that is alive, that is changing. It leads him back to the Sufi rituals prescribed during prayer, which he experienced as a child with his grandfather who led such rituals as a Sufi master, a ritual that took place in secret and which could transport the partaker into a trance. But this rhythm was also present in his day-to-day life, when his grandmother continually muttered the verses in the Sufi rhythm or moved her lips wordlessly, running a string of beads through her fingers. This build-up and constant repetition of the Sufi rhythm can lead to a trance-like state, which for many signifies the absolute path to religious knowledge.

Samir Odeh-Tamimi has linked this physical, meditative ritual with Mansūr Al-Hallāğ’s philosophical insight. In the Sufi rhythms of his texts, Odeh-Tamimi has given the words, "she is not him and he is not her, and only she is him and only he is her," to the singers as a recitative. In the hand-written score, one can see these words graphically distributed on the page so that their movement in the room can be recognised, the movement through the room in which the audience sits.

The composer interrupts these passages that are dominated by this rhythm with musical interludes in the form of sometimes wild, loud, dense sounds. Often, Odeh-Tamimi builds clusters of neighbouring notes around the central tone F-sharp, producing sharp dissonances and creating passages of hightened tension in the process. They interrupt for a moment the flow of the Sufi rhythm, which induces a trance-like state. They lead into the musical world of Samir Odeh-Tamimi, which he developed after immersing himself in the music of Arnold Schönberg, Younghi Pagh-Paan and many contemporary composers.

It is a world through which he has been accompanied by Mansūr Al-Hallāğ’s philosophy, resulting not only in works that use texts by Al-Hallāğ but also lots of sketches that he had in mind during the working process and which he inserted into "Mansūr" at specific points. During the compositional process, his thoughts became more concrete and, looking back on what he had already written, individual notes emerged that he then placed throughout the room. During the interludes, Samir Odeh-Tamimi works without concrete texts, with breathing sounds in the voices and open vocals, written in Greek because for him, this language embodies the archaic fundamental form of language. Again and again, there is a reduction to a deeply tranquil sound from these musical spaces, from which the voices are able to soar anew.

While the male voices ruminate for a while over Mansūr Al-Hallāğ’s confusing mysteries – "he is not her and she is not him" – dominating the soundscape, the female voices suddenly appear. They sing about Allah and articulate Mansūr Al-Hallāğ’s knowledge: "The one with knowledge is the one who can see, and knowledge is eternal, the one with knowledge exists through his knowledge."

This Arabic text is supposed to be articulated like a German text by the choir. Samir Odeh-Tamimi expects an inner understanding. And those who have understood are persuasive in their assertions. This attitude can be traced back to a key experience that the composer, who has lived in Germany for 24 years, had. Someone read a German poem aloud and, even if he wouldn’t have been able to translate every word directly, he understood the secret of the text.

In the original handwritten score of "Mansūr," there are few corrections. Samir Odeh-Tamimi felt challenged for the first time, not simply to cut, copy, paste and rework material during the compositional process, but also to document the knowledge he gained in his own handwriting, handwriting that perfectly shows his logic.

In the score, Samir Odeh-Tamimi notes tempi that range from "legatissimo" to "as fast as possible," suggesting that it is not purely a matter of speeding-up but more of changing the inner attitude, a process of letting go not unlike what we find in a Sufi ritual. Right at the end only individual syllables are left. Concepts fade away, but the knowledge remains.

Margarete Zander, 07/2014 | Translation: Celia Wynne Willson