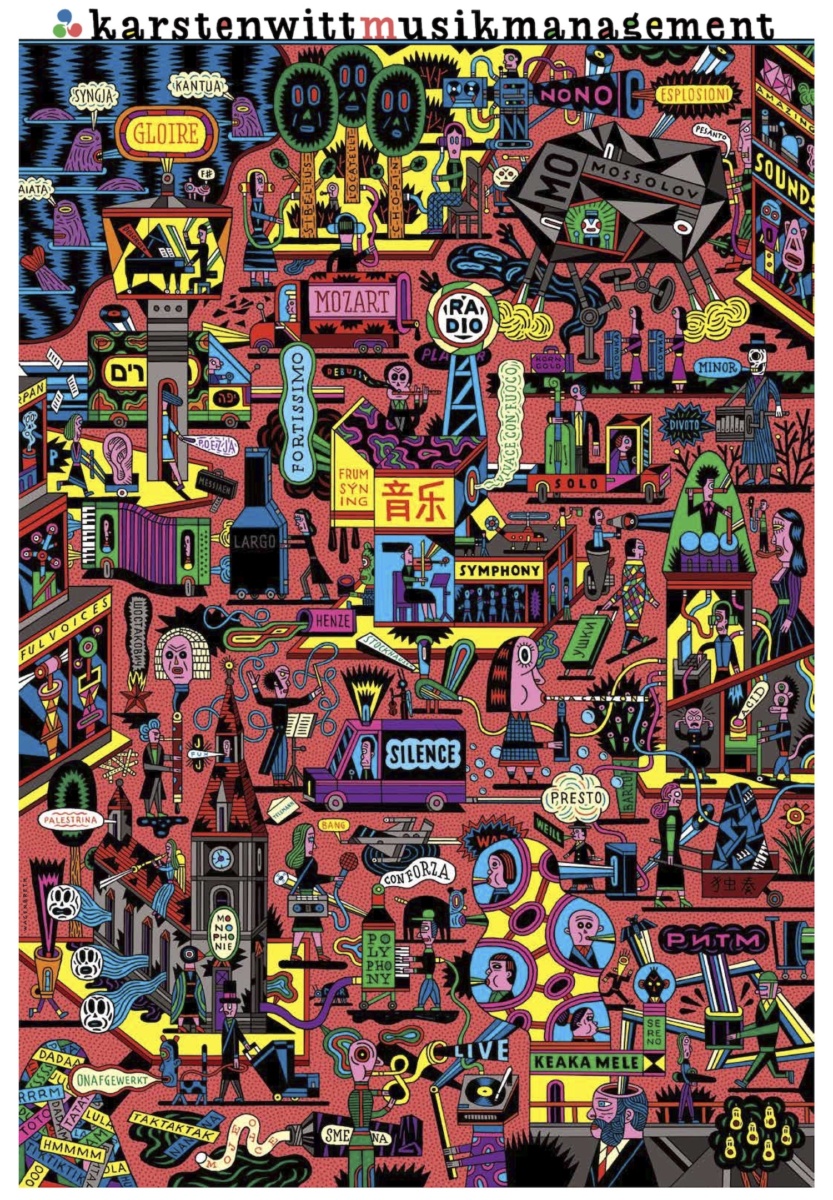

We are celebrating 15 years of karsten witt musik management. Our magazine published for this occasion (DOWNLOAD) presents current activities and positions around our artists as well as memories of one and a half decades full of music. This potpourri of news, portraits and background reports starts with an interview.

At the beginning of the year, we had a visit from the editors of the monthly magazine Kreuzberg Welten, who conducted the following interview with Karsten Witt, which they have kindly released for publication.

Karsten Witt Musik Management is celebrating its 15th anniversary in 2019. What led you to settle here in Kreuzberg?

Initially, my wife and I were compelled for personal reasons. The district was not as hip as it is now; Prenzlauer Berg was the trendy spot. We were coming from London, where we lived in the multicultural Eastern part of the city, off Brick Lane – so for us Kreuzberg was a natural choice. We were lucky to find shelter in a large office building and started out as subtenants of two rooms. A further advantage is that we are quite central here. The Konzerthaus, the Staatsoper, the Komische Oper and the Hanns Eisler Academy of Music are only ten minutes away by bike.

And why Berlin, precisely – couldn’t you have stayed in London?

London is a wonderful city for tourists; but living and working there is not so easy, and furthermore very expensive. Moreover, the city already has a lot of great international artist management agencies, which we were friendly with and didn’t want to compete against. On the other hand, for our industry, Berlin was still rather empty. There was the long-venerated Konzertdirektion Adler. But Sonia Simmenauer, KD Schmid and the branches of the London offices only came later. Of course, a music metropolis like Berlin is also practical for us since so many artists and colleagues work here, owing to the many orchestras, concert halls and opera houses. That saves us travel time and costs.

Previously, you were artistic director of the Vienna Konzerthaus, president of Deutsche Grammophon and CEO of the London Southbank Center. Why did you start your own company?

Above all, early in my studies I had founded the Junge Deutsche Philharmonie, out of which the Ensemble Modern and the Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie later emerged. I managed them for 18 years, acting as the secretary of self-managed orchestras in which the musicians had the final word – without actual superiors, without subsidies, without outside control – almost like companies of our own. Even the Vienna Konzerthaus was, during my time there, an institution with little external control, in which I still had the essential artistic and economic responsibility. I think this suits me. I take – together with the members of our team, naturally – responsibility for the risks we take. Such a setup is rare nowadays. But it’s appropriate for an artistic institution, which in order to survive must constantly produce new offerings.

But isn’t one always dependent, for example, as a company on its customers?

Sure, one is always operating within a network of dependencies. In our case, most of all to the promoters who engage our artists; but naturally also to the artists whom we represent, our employees and our landlord – who just increased our rent by 50%, incidentally. But in the end, we can decide for ourselves whom we represent and collaborate with – and whether we still want to afford Kreuzberg.

What exactly does a music management do?

The foundation of our work entails advising promoters of classical music concerts and providing programming. Based on my experience, I can also offer consulting for the construction of new concert halls or the restructuring of organizations. And naturally we also act as consultants to our artists, whom we usually represent worldwide exclusively.

The advisory and consulting role is evident. But why does one still require an intermediary, if nowadays everyone can communicate with everybody else directly online?

We ask ourselves that same question on occasion – unfortunately there is far too much redundant communication which eats up our time. But that's why busy artists need an office to do this work for them. Negotiating the conditions of an engagement is easier for a mediator who oversees the interests of both sides. And, with the help of our contacts, young artists with little experience can find their way.

In your profession, it’s primarily about building and maintaining relationships.

That's right. We have to be nice to everyone. But this also has to do with the music itself. Musicians want to bring joy to their audiences – or at least have them see the world in a new light. This only works with a positive attitude. I think this charitable stance, embodied by all participants in this game we call classical music, is what motivates most of us to work for it every day.

And how does one manage to maintain these relationships all over the world?

I must admit I underestimated this when we started. From the start we decided to work for artists in general management only, because we do not only care about sales, but about comprehensive support. And we began right away in every possible category: soloists, conductors, singers, composers, various ensembles, touring orchestras, and so on. It was only later that I realized there are many different networks in our classical world, which are not connected amongst each other except by the major concert halls and record labels: opera houses, orchestras, chamber music, early music, new music, etc. To serve all these networks, one needs a larger team. Add to that the many regions that one must travel to. And while the traditional classical music scene in Europe is facing major challenges, Asia and Eastern Europe are experiencing major growth.

How many employees do you have?

We started out 15 years ago with four. Since then, Maike Fuchs and Xenia Groh-Hu, who have been here since the beginning, are now co-managing directors of our company, which employs about 20 people, including part-time employees and interns.

Are there different departments? How does that work with so many people?

In principle, there are two colleagues working for each artist, one for strategic planning and development, the other for project management. And then there is a certain degree of specialization on certain genres: singers, instrumentalists, conductors, new music, touring. Finally, there are the key functions: Website, IT, Human Resources, Accounting, Office Administration, which in part are distributed internally and in part are staffed by specialists.

And what skills must one have to work with you?

First and foremost, common sense, good organizational and communication skills, and a healthy dose of perfectionism. Everyone must be able to speak and write in English. Other languages are useful; we have staff who speak Mandarin, Russian, French, Spanish. And everyone needs at least a basic knowledge of music. Most of us have studied musicology or music, and play instruments, participate in amateur orchestras, or sing in choirs.

It all sounds very logical and pleasant, the way you go about your work here. But isn’t it primarily about nabbing stars from your competitors?

It’s a question of attitude. We are mainly interested in the music. Among the few stars of classical music there are even fewer interesting interpreters, and they usually have no reason to change their agency. We also do not actively approach artists. Fortunately, from the start there have always been plenty of outstanding artists who want to work with us and find their way to us.

Can you tell us how to make money with such an attitude?

Our artists pay us primarily in the form of commissions on fees for performances that we arrange for them. So, in the end, we benefit from the organizers who hire our artists and pay their fees.

So that means you do all the preliminary work before you get paid?

Correct. Organizers usually schedule things one to two years in advance. That's how long it takes to harvest the fruits of our labour. This concerns not only the finances. It’s also how long it takes until a concert we've arranged is happening, or a new composition that’s been commissioned will be heard.

That sounds risky.

Assembling such a company is obviously not a secure investment, and one needs to remain calm and be persistent. But nobody does this primarily for the money. Incidentally, the same goes for our employees as well. Working here is more of a lifestyle choice. We love music and our artists and like to gad about backstage – always supportive and attuned to the stage.

What is your employees’ perspective – do they also want to start their own company one day?

It’s not so easy, as mentioned. We are currently working on a model of how our employees can be involved in the company. Since building my self-governing orchestras, this seems to me to be the right path forward.

You’re located here in Kreuzberg, amid lots of start-ups. Wouldn’t it be quite normal to sell the company one day?

Is that really normal? Companies that built exclusively on communication are entirely dependent on the people who carry them. Should they be sold, then? In our industry, at least, this usually goes awry.

After 15 years, do not you want to start something new as an entrepreneur?

I am thinking more about new projects, such organizing our own concert series. But for me, this "work" is primarily an end to itself. Naturally, it is exhausting at times – the constant traveling can get to you. But in the evening when we find ourselves at a concert or the opera, we are grateful that we are able to live such a privileged life.

Published with kind permission of Kreuzberg Welten (KW).