We are publishing the interview, published in Italian in the online magazine MusicPaper, with the kind permission of the author and the publisher.

by Gianluigi Mattietti

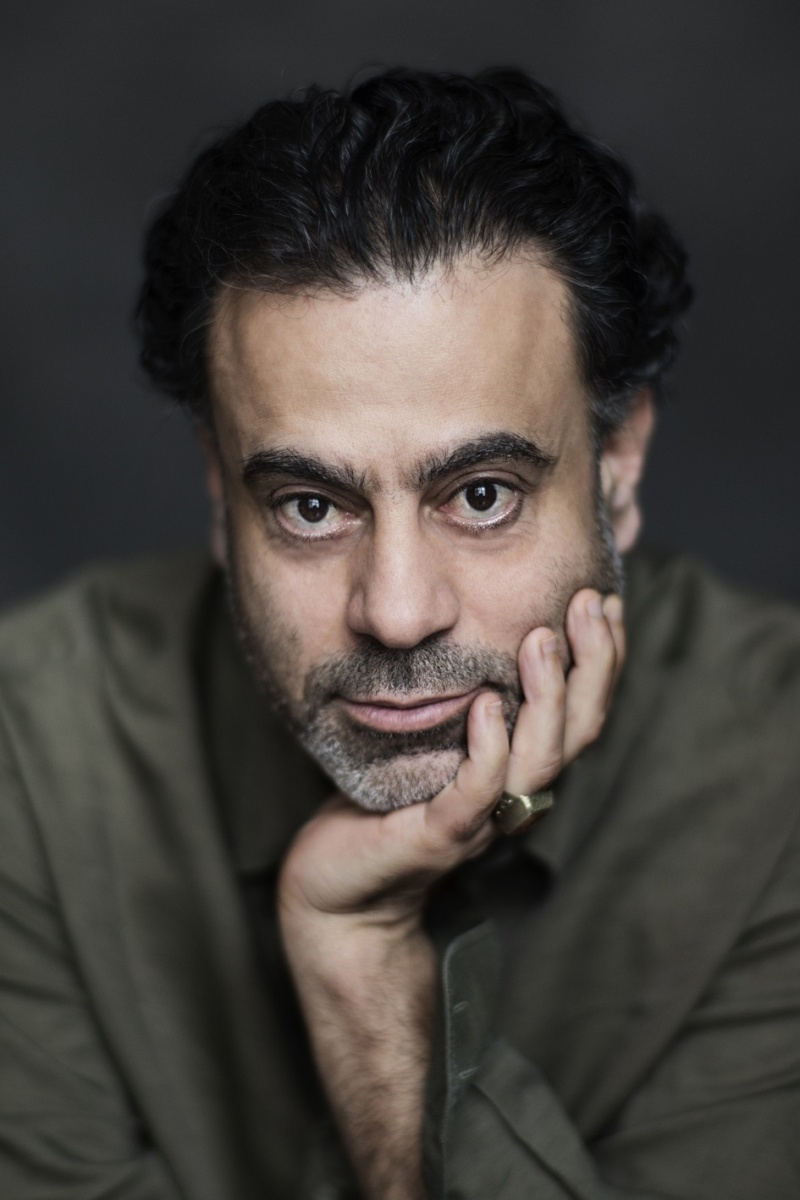

He has lived in Berlin for 20 years. However, he was born in 1970 in Jaljulya, a small village near Tel Aviv. Samir Odeh-Tamimi has established himself with his vehement, dramatic, rhythmically intense musical language, which unfolds an archaic power and mixes elements of the avant-garde with echoes of Middle Eastern music. A new piece by Odeh-Tamimi entitled Roaïkron for six percussion instruments, specially commissioned for the Christian Benning Percussion Group, was performed at the Biennale Musica in Venice on 7 October. We start here.

Where did the inspiration for this composition come from? And what does this enigmatic title mean?

It is a double name that comes from the fusion of ‘Roaï’ and ‘Kron’. Kron is an abbreviation of the Greek word Krónos, Saturn. Roaï comes from ‘roaïa’ which in Arabic mythology indicates dreams, or rather premonitions that happen in the morning, like divine messages about things that might happen. Roaïkron therefore indicates a message coming from Saturn and the giant rings orbiting the planet, made of tiny particles and very large fragments of matter...'.

And how do you translate all this into music?

It all stems from a dream I had two or three times in my life: I dreamt of hearing music coming from those rings, music as rich in different sounds as the materials that make them up. So I tried to create an accumulation of rhythmic materials with the different tonal colours of the percussion instruments, skins, metals, woods and so on. But I did a lot of drawings first, something like the material for this piece, because I always like to transfer my ideas into drawings before I start with the score.

This commission was a really extraordinary opportunity for me because I love percussion, I have written many pieces for these instruments, and I think they correspond very well to the sounds I imagined. These rhythmic materials are layered in a complex, often unpredictable fabric, like dust particles floating in space around us, but with explosive moments and zones of nervous calm, like after an explosion or fire.

The performers also articulate spoken fragments that sometimes turn into real screams with a primitive character, and at one point they leave their place on stage to move around the audience with drums in their hands.

Let's rewind the tape. You are now an established composer, having just returned from Harvard University, where you gave a composition masterclass at the invitation of Chaya Czernowin. But tell us about your musical training.

I now have German citizenship, but I was born and raised in a small Palestinian town in Israel. A very small village, where we are Arabs but have Israeli citizenship. There I started to study music as a child. First the recorder, then the organ and the piano. My piano teacher was a Russian Jew: I went to him every day to play the piano, because I only had an electric organ at home.

When I was 12, I started to compose songs. I had a synthesiser with microtones, a very old instrument that Farfisa produced for the Arab market. You could change the pitch of the scales. And with that instrument I played with an Arab group called Angham: there were about 15 of us, with traditional instruments, such as the oud, the nay, the qanun, the riqq, and we played Arabic music, both traditional and pop. But when I was 18, I moved to Greece, because I wanted to study composition seriously.

Did you get a scholarship?

No. For us Israeli Arabs, there are no such opportunities. I was in love with the Greek mythology I had studied at school, so I decided to go to Athens. Above all, I wanted to go to Europe. When I got there I said to myself: ‘OK now I am in Europe!’ But I had no money and it was not possible for me to study music. I tried all avenues for three years. There was a very good music school in Thessaloniki, I tried there too. I could only attend a school to learn the language. But I also studied Greek history and mythology.

I also travelled a lot around Greece, and earned some money playing with my synthesiser: Arabic music, Greek music, popular music. At that time I knew nothing about contemporary music. For me there was only popular and classical music. And Beethoven was for me the composer par excellence.

And when did you move to Germany?

I was 21 years old. A friend of mine, who was also from Jaljulya, lived in Kiel. He used to tell me a lot about Germany. He would say to me, ‘Samir, all the famous composers are German: why don't you come to Germany? Come to Kiel, I will help you a little'. So I moved there and started studying musicology at university. I learnt music theory and the German language well. To support myself I worked as a waiter in restaurants. I worked for ten years in restaurants in Athens, Kiel and then Bremen... it was a very hard time.

What about the study of composition?

That was my goal, not to study piano or musicology. But I had no guide, no teacher to direct me. It all happened a bit randomly. I enrolled at university because it was the only opportunity I could find to study western music. I did not have a clear idea about composition, I did not yet know contemporary composers, but I knew that I was not interested in composing ‘classical’ music. However, in the University's Music Department there was a very good library, very modern, full of materials and well equipped. There was a room for listening to music and there were many scores.

One day I listened to Schoenberg's Quartet No. 4. It was a revelation: I discovered something I did not know. I started to study twelve-tone music. After Schönberg, I discovered Berg and Webern, and then Luigi Nono and Lutoslawski and Xenakis: I realised that this was my path!

So that listening room was crucial?

Yes, there were so many recordings and scores. There I also discovered the music of Scelsi, Klaus Huber and many other composers, including Younghi Pagh-Paan: I heard that she taught in Bremen, and I wrote her a letter telling her about me and my desire to study composition. I had no answer for several months. Then one day, or rather one night, because it was already one o'clock, I received a phone call: ‘Hello Samir, I am professor Younghi Pagh-Paan, do you have plans tomorrow?’ ‘No’ ‘Then come to Bremen. I'll be waiting for you at 11.00 am in room 125 at the Hochschule für Künste’ 'OK'.

The next morning I took a train and in two hours I was in Bremen. There was a class, also with other composers. I showed her some things I had written, they were just sketches, nothing complete. She introduced me to the others: ‘This is Samir Odeh-Tamimi, maybe he will be in our class...’. The following year, at the age of 28, I became a full student in her class, but at that Hochschule I also took analysis classes with Günter Steinke, a fantastic composer. My first piece was also performed in Bremen. It was a work for bass clarinet, cello and percussion. Although I later destroyed it, it was really very exciting to hear my music for the first time!.

Then there was the piece written for Donaueschingen?

Yes, that was another decisive turning point. In 2001, I had moved to Berlin, although I continued studying with Younghi Pagh-Paan in Bremen until 2005. At first it was hard in Berlin, but it is the ideal city for a composer. Kiel and Bremen were like small villages in comparison.

In 2003 I received first prize at the Elisabeth Schneider Foundation Composition Competition for a piece called Ja Nári for trumpet, horn, bass trombone and percussion which was performed in Freiburg. Armin Köhler [then artistic director of the Donaueschingen festival] was present at the concert and he immediately commissioned a piece from me: so I composed Gdadrója for three sopranos and orchestra which was performed at the Donaueschinger Musiktage in 2005. Since then, I have started receiving many commissions and have been able to dedicate myself exclusively to composition.

As a composer, what has been the evolution of your musical language, from Gdadrója to recent works such as the opera Philoktet, performed in Stuttgart in 2023?

It has been a long journey, although I think my musical language has been clear and well-defined from the beginning. My early works were quite short, concentrated, very powerful, like Gdadrója where so many things were happening even simultaneously: it was music thought like a scream, which didn't give you time to think. Láma poím... for orchestra and oud was also a massive piece, full of energy. At that time I was very attached to the idea of mass, also influenced by reading Elias Canetti. Then the study of mythology changed my music, which I began to think in more and more archaic and ritualistic forms. I was also greatly inspired by the music of Jani Christou. Now my works develop in a broader time frame, with an idea of theatre. I work more with space and time.

Your catalogue contains various cultural references to antiquity: from Greek tragedy, such as in Philoktet, a work by Sophocles, to the Sumerian death rituals that inspired Gidim for orchestra and electronics. But there are also repeated references to Arab culture and the plight of Palestine: the pieces on texts by Mahmoud Darwish, considered one of the greatest poets in Arabic (Ahínnu, Hálatt-Hissár, Námi); Oh people, save me from God for five voices, which combines texts by the medieval Islamic mystic Mansur Al-Hallaj with verses by the Syrian poet Adonis; Jarich, for three voices and electronics, with echoes of Palestinian ritual chants; Timma for choir and ensemble, inspired by an ancient kingdom in southern Arabia; the opera L'Apocalypse Arabe ( 2020), which tells the fate of the Arab world. ..

At a certain point in my career, I wanted to reconnect with the Arab world in a very strong way. When I was in Bremen, in the electronic music studio, I even managed to computer-analyse the voice of Sheikh Abdul Basit, a famous Qur'an reciter from Egypt. He had moved me greatly when I was a child. His musical practice was incredible, full of ornaments, vibrato, glissandi. I realised very early on that no Western musician would be able to imitate him, not even close. So I started working on the smallest nuances of Arabic music, on the microtonal dimension, on the smallest differences in duration. Perhaps the most important piece in this sense is Mansúr for large choir, brass and two percussionists, where I used texts by the Sufi mystic Mansur al-Hallağ.

My grandfather was a Sufi singer and I grew up in a family that practised Sufism. During my youth I was very fascinated by these ceremonies, but for their musical aspect, not for their religious content. Even today I am still impressed by these rituals, their archaicness and depth, their level of ecstasy and concentration. The Muslim tradition does not mean much to me nowadays, and I am not religious, but in my music I have made reference to these rituals in the project Into Istanbul, realised with the Ensemble Modern, in some parts of my opera Leila und Madschnun, in Ritual for Orchestra.

In many of these composer's works, there are explicit references to the war, to the refugee drama, to the connection with your homeland and family. Do you sometimes return to Jaljulya?

Yes, but more and more rarely, given the situation in Israel. My parents came to visit me here in Germany. They even heard a piece of mine performed in Tel Aviv. I am not sure if they can understand my music, but they have a lot of respect for what I do. I am also the only one in my family who took up music. I had six brothers and sisters, but three are dead....

How do you judge the current situation in Israel?

Unacceptable. In my family we are Israeli citizens but of Palestinian nationality. For me it is really all a big mistake what has happened this past year. I don't support Netanyahu and I don't support Hamas. And it makes no sense to create a Palestinian state separate from an Israeli state. I believe that what we need is to live together, as Jewish citizens live together in Israel who are all of different nationalities. We need to be able to live together, and in peace. But with the same rights, of course.

Gianluigi Mattietti, 9/2024