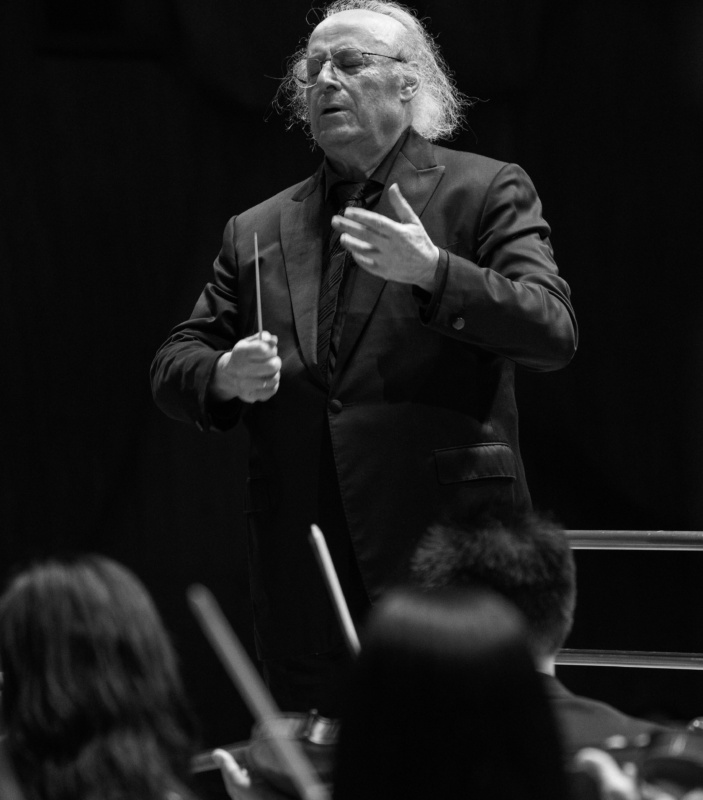

With the world premiere of Hèctor Parra's opera Les Bienveillantes, directed by Calixto Bieito, Peter Rundel made

his debut appearance at the Opera Vlaanderen. A few weeks before the

premiere in April 2019, we spoke to him about the new work and his role at

the centre of major opera productions.

When did you first become interested in Les Bienveillantes?

As soon as it became clear that this was a project for me, which was

about two years ago, I immediately went out and found the book by

Jonathan Littell. I only knew about it beforehand because there was a

huge scandal in France over whether it is permissible to recount the

crimes of the Nazis in the form of a first-person novel. Never in my

life have I had as difficult a reading experience as I did with this

book. It did something to me that probably explains, in part, the

scandal it caused. As the reader, you start to identify with the novel’s

narrator and protagonist, an SS man who is confident in his ideology

and who received his philosophical training within this machinery, as

well as someone who is an active participant in it. This is absolutely

terrifying and deeply troubling, yet at the same time fascinating. The

big question, of course, is how to bring the essence of the novel, this

identification and dialogue with the narrator, to the stage in a musical

form. The first step was to find someone to distill and linguistically

compress this colossal story. As in the previous opera,Wilde in Schwetzinge, where I worked with the same production team, Hèctor Parra turned to Händl Klaus for the libretto.

So you were involved in the project even before it was clear who would write the libretto – that's rather unusual for a conductor.

I’m on friendly terms with many composers and therefore often know

about their plans early on. Sometimes, I also try to seek out production

possibilities for certain ideas. That's one thing that keeps me busy

and interested as a conductor: not just being the musical midwife, but

also helping make certain ideas a reality through my contacts. And of

course, being involved from the beginning is the most satisfying way of

working together.

What is important to you in the role that you play in the production process?

I never cease to be fascinated by opera as an art form; the fact that

so many types of art and artists are involved from different backgrounds

and with completely different experiences. As the musical director I'm

virtually at the centre of the process, alongside the director. There, I

see myself primarily as an advocate for the composer and the music as

well as the singers. At the same time, I have to attend to the needs of

the other artists and their different perspectives. This is a kind of

utopian model of cooperation: everyone wants to contribute and be

represented in the end product. To play a part in developing and

mediating such a piece is a fantastic opportunity. It’s a tremendous

luxury that our society still provides us with such a playground to

develop these ideas, but apparently we still have a need to tell and

interpret stories on stage – this is something that particularly defines

our culture.

Are there any productions you recall which particularly provided a utopian model of cooperation, as you put it?

Having grown up in the freelance scene, musically speaking, I have often

searched for working conditions that facilitate collaboration. For

years I was the musical director of the Wiener Taschenoper. That was a

long time ago, but there were a few examples there that left a

particular impression. For example, our production of Michaels Reise

by Stockhausen, a collaboration with the Ensemble Musikfabrik and La

Fura dels Baus, was particularly satisfying for me, both in terms of the

process and the end result.

It's not easy to single out individual works from your long list of opera engagements, sincethe label ‘exceptional’ applies to so many of the productions. Were there other pieces besides Michaels Reise that were particularly important for you?

Das Märchen in Lisbon was a very significant experience.

This was the perfect example of an ill-fated production, primarily

because the composer, Emmanuel Nunes, only finished the composition at

the very last moment. It was a torturous process bringing the piece to

its world premiere. The experience still resonates with me because the

opera hasn’t been performed since and the music is terrific. Also

because of the material itself. Goethe's fairy tale [The Green Snake and

the Beautiful Lily] is an enigmatic story, a kind of a Magic Flute-esque

world with snakes and princes and many interpretive possibilities. I

think it's a masterpiece; I hope that an opera house will finally decide

to tackle it again.

That is an extreme example, but compositions being finished at the very last minute is probably a rather common occurrence when staging new operas.

That's just the way it is. It’s also the case in the concert world – I’m

thinking of one I just gave in Donaueschingen in Germany. As a

conductor, you have to keep a cool head, radiate calm and create a

genuine sense of security for the others. But there are of course

extreme situations, where you have to put the ball back in the

composer’s court and say: ‘either we discuss making some cuts or it

won’t be ready in time.’

Many of the projects you have been involved in have

stretched the physical boundaries of standard opera productions. At the

Ruhrtriennale you have conducted pieces such as Die Materie, Prometheus and Leila und Madschnun in a huge space. Do you have a particular affinity for such monumental performances?

It’s definitely part of the appeal to be at the helm of such an enormous apparatus: choir, soloists, orchestra, in some cases electronics, often distributed across a large space. But to be honest, what connects to opera most of all is the voice. I love the voice. Maybe it's because I was a violinist, and for melody instruments the ideal sound is that of the human voice. I have a tremendous amount of respect for opera singers, because I know what it means to be onstage, singing without sheet music and embodying a role. For me, this sense of exposure, this vulnerability of singers is something that goes beyond what happens in a normal concert. It’s precisely because of this risk that a special kind of magic or beauty can appear. For me, singers are like tightrope walkers. I can be the one who breathes with them, who gives them a sense of security, who carries them and supports them. I'm the safety net, so to speak. This is actually not just relevant to my work with singers, because so many elements are interlinked in the opera. If one thing is out of place, the whole thing threatens to collapse like a house of cards. And of course, although you do everything you can to prevent it, you also know when to let go, so that, despite everything, you can create a sense of freedom. When this works, it’s the most beautiful thing.

Nina Rohlfs, January 2019. Translated by Kathleen Heil.