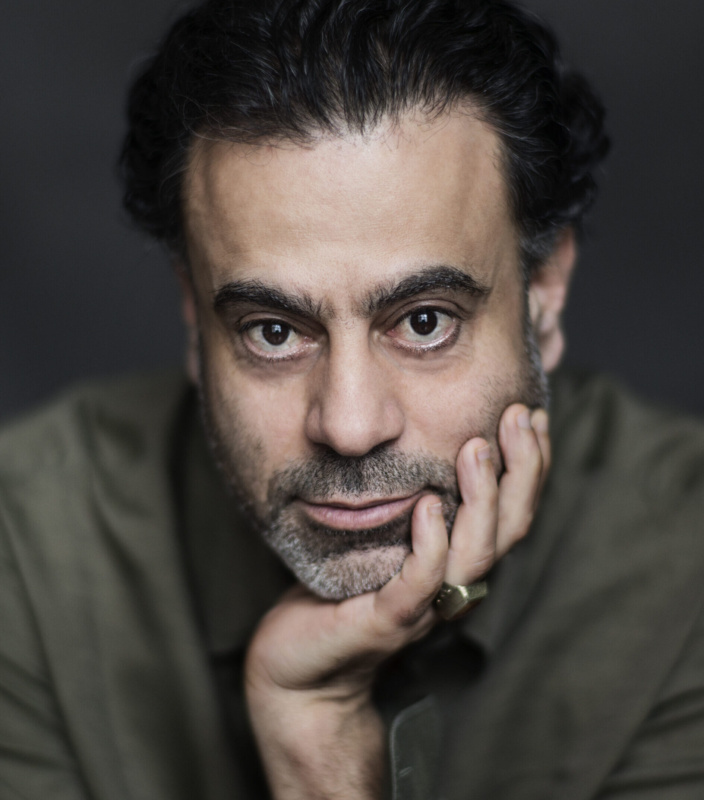

The Osnabrücker Symphonieorchester and Academic Symphony Orchestra Volgograd commemorated the victims of war and terror in 2015 with concerts to mark 70 years since the end of the Second World War, thereby creating scope for exchange, discussion and mourning. In May 2015, the composer Jens Joneleit accompanied the orchestras and his work Ehrfurcht (Andacht) (“Veneration (Reverence)”), composed especially for the occasion, to Moscow and Volgograd (formerly Stalingrad). He took the opportunity to discuss his piece, hear opinions on the current political situation and talk to war veterans about their experiences.

The performance of the work on 9 May at the site of the crushing German defeat in 1943, today one of Russia’s most important memorials, was also attended by the German Minister for Foreign Affairs Frank-Walter Steinmeier, who was in Russia on a state visit, and his Russian counterpart Sergey Lavrov. Together with approximately 10,000 other audience-members, they heard a light, restful piece that in no way tried to depict the horrors of war. “I didn’t want to depict the end of the war with a particular atmosphere,” explains Jens Joneleit. “The music ought instead to bring something of the present day to this period in time. As I tackled the topic through the Osnabrück orchestra’s commission, my own family history played an important role – my grandfather was a soldier in Russia, a parson in the field. After this experience he always had the urge to convey to me the horrors of war, the senselessness, the terror.” But the overall tone of his piece is influenced most of all by his grandmother’s stories. “She said that when war is over, it’s not like a light switch that you can turn off. It takes a long time to come to terms with the horrors that one witnessed. In the first few weeks a sense of ambivalence dominates, there’s an uncertainty as to whether peace will remain or whether war will flare up again. I tried to convey this in my music. The listener is transported to a place where he can feel that something is shifting, something is becoming lighter but something black appears – and then it remains grey. This limewash grey, between black and white, this uncertainty is the central theme of my composition.”

It seemed as though the project would come to an abrupt end when the political situation in Ukraine escalated. “Shortly after I started composing, there were protests in Kiev's Maidan Nezalezhnosti square,” explains Jens Joneleit. After the Crimean crisis and the shooting down of the aeroplane over eastern Ukraine, sponsors pulled out. “So for me there was also an acute, very concrete state of uncertainty. I had composed two thirds of the piece and didn’t know if it would ever be played.” Feelings of ambivalence and uncertainty oversaw the compositional process all the more when he travelled to eastern Ukraine three times on private visits. “It was very distressing looking into the empty faces of Ukrainian soldiers who couldn’t look you in the eye when you talked to them. It really shocked me: I’m writing a piece to mark 70 years since the end of the Second World War and here I am now, a 46 year-old in the middle of Europe, talking to a Ukrainian soldier in front of a T-72 battle tank that is fully loaded and ready to be fired.” The memories and stories of his grandfather, who was stationed near Kiev, also accompanied Jens Joneleit on these visits. “That I was now following in his footsteps with my piece, in the very region where the war ended 70 years ago and where a new war is now taking place, was a strange and appalling feeling. The awareness that the current situation can change at any moment is also in the piece.”

One can be sure that concerts are rarely as politically and emotionally charged as the joint performances in Moscow and Volgograd, programmes rarely discussed so critically about their suitability for the historical situation. And yet before the two orchestras travelled to Russia with the piece, concerns were brought to Jens Joneleit’s attention that his tranquil and reverent piece might be met with rejection. This is because, despite the loss of approximately 26 million Soviet citizens in the Second World War, 9 May is celebrated as Victory Day in Russia, with fireworks, military parades and expressions of thanks and flowers for the veterans. A confrontational interviewer for Russian television boiled the doubts down to the reproach: “We are celebrating and you are offering us a requiem”. Jens Joneleit retorted with, “But I can’t come with victory music,” and talked about how the soldiers of the Soviet Army pushed the Germans further and further back until they put an end to the Nazi horror. “I am the result of their acts,” he says. “My parents’ generation grew up in the rubble of war. They knew exactly why there was rubble: the Germans instigated a colossal war. They passed on this legacy, this coming to terms to their children. And the veterans often grasped this much quicker than listeners who were born after the war. They felt more provoked with regard to the tone of my music.”

“However, these were only solitary experiences,” he concedes and says that he has never given so many autographs than on this trip. “And when you’re giving out autographs, people ask critical questions too. They want to know something from you, they won’t just go to the concert and say, ah a world premiere, how nice.” His encounters with war veterans were particularly moving. “Lots of veterans came to me after the concert in Volgograd and embraced me, half crying half laughing. Just the fact that we were there, taking into account the crisis in Ukraine, made them very happy. Many of them said they cannot comprehend what is happening at the moment – this playing with fire. One has to give it to the Soviet veterans: they have a bigger perspective than the younger generation in Russia.”

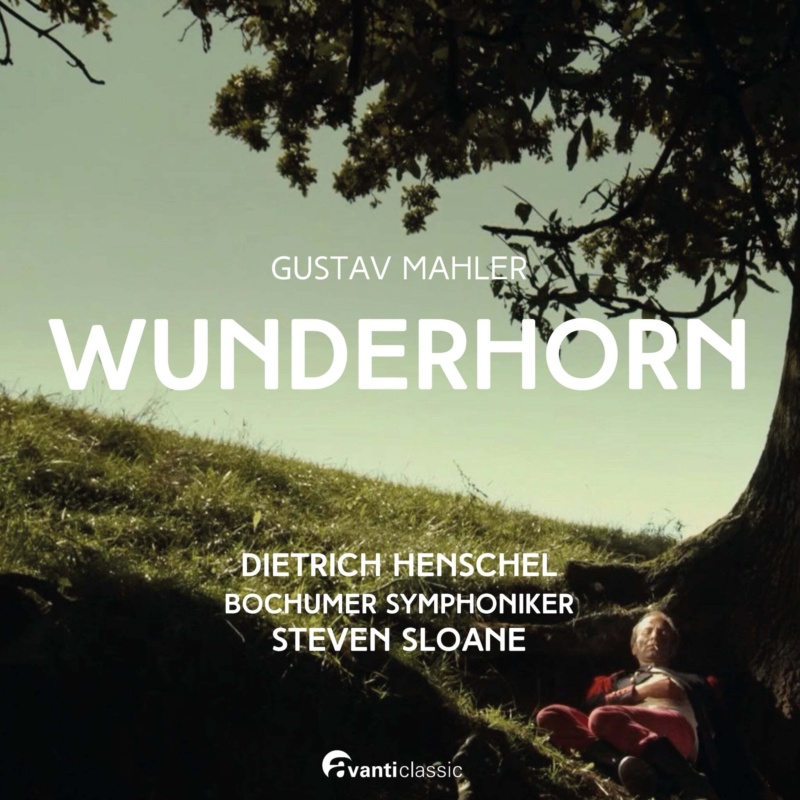

Those who seemed to call for triumphant victory music the least were the veterans of all people. “They were the ones who said, Jens, you’ve hit the right note,” says the composer. “For many of them, Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 7 was simply too loud.” The “Leningrad” symphony, that was completed a few weeks after the German attack on the Soviet Union, was the second work on the programme in Moscow and Volgograd. “It’s music that aimed to inspire listeners at the time not to give up and naturally has a very different tone compared to my work. The difference couldn’t be more extreme.” Before the tour, Jens Joneleit favoured the eighth symphony. “Shostakovich wrote the eighth to throw critical light on his seventh and his perspective at the time. It is also victory music but above all it reveals the torments of war. He experienced the beginning of the Siege of Leningrad but fled shortly afterwards to the east. There, no one had the foggiest idea what it was like on the front. He was shocked after speaking to injured Soviet citizens and regretted having engulfed people in the war and in their misery with his seventh symphony that was so apt to be used as propaganda. This critical tone is evident in the eighth.” In Moscow, Jens Joneleit observed that many concert-goers shared his opinion. “Russians who are familiar with music know about Shostakovich and the problems he had with the Soviet state. Many said, but we have music for this occasion! The eighth symphony contains music composed with a critical eye, why isn’t that being played?“

It was not only the music connoisseurs in the audience who welcomed the stark contrast of Ehrfurcht (Andacht) alongside the symphony. “Many were glad to hear a piece that permitted mourning. Of course 9 May is a victory day in Russia. But the celebrating and the fireworks cannot be mentally endured year after year. A veteran said to me: ‘Finally someone is giving me something to make me cry.’ I found that phenomenal and it just goes to show that this project was really worthwhile.”

And this is how Jens Joneleit sums up the experience, despite his sympathy for the reluctance and ambivalence of the German politicians who struggled with visits to Russia to commemorate the Second World War given the current crisis: “I personally find it momentous that we took the step to go there and to carry on with the project, and I also think it is good that the commemoration was interwoven with the current situation. That is why we have these occasions and memorials: to ensure something like this never happens again.”

Nina Rohlfs, 06/2015 | Translation: Celia Wynne Willson