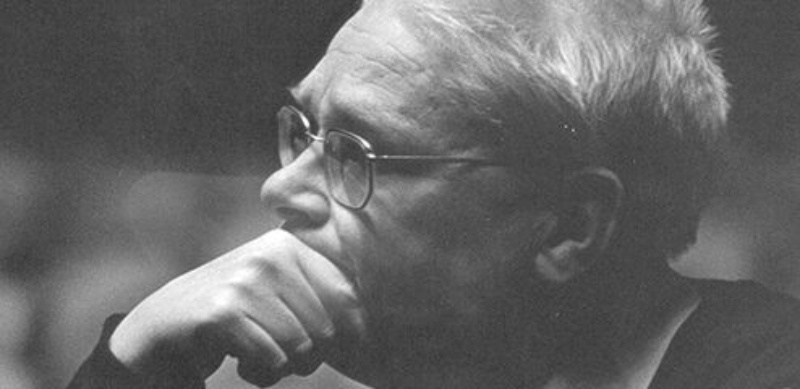

One of the reasons György Ligeti’s music continues to fascinate audiences is that the composer constantly reinvented his musical style and was always searching for something new; a consequence of his incredible openness to a wide range of musical styles across different genres and cultures. His son Lukas Ligeti has inherited this curiosity and has devoted a large part of his career to crossing the boundaries between different musical traditions, both as a composer and percussionist and in his role as a Professor at the University of California. Christoph Wagner met him to talk about his development as a musician, his fascination for African music and his relationship to his father. Here we reproduce excerpts from their conversation with the kind permission of the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, where the full-length interview was originally published (02/2019).

What kind of a person was your father?

My father was very curious, always on the search for something new. He was always engaged with new styles of music, and was constantly developing new interests. This is how he discovered jazz, which he found very interesting: less so free jazz and free improvisation, more jazz with improvisation in pre-determined structures. What particularly impressed him was – as he called it – the ‘elegance of jazz’. With that he meant the spontaneous control over the economy of tones; this led him in the direction of cool jazz: Miles Davis from the beginning of the 1960s was one of his favourites, as well as the pianist Bill Evans, and also Thelonious Monk. He also liked early jazz, and to an extent rock jazz, but only up to Weather Report or early Mahavishnu Orchestra. He once played me ten cassette tapes of the complete history of jazz. He also liked some rock music.

Did your father influence you in your musical career?

I was a late bloomer, musically speaking. As a child I played a bit of piano, but never wanted to practice so I gave it up again. I first started to take music more seriously at the age of 18 – so, around 1983. I used to swap cassettes with my father, in a sort of “hey, listen to this!” way. Whilst doing my homework I always listened to radio, for example Neue Deutsche Welle – Fehlfarben, DAF! But somehow I never really felt at home with this music. I also listened to a lot of jazz, free jazz, as well as punk and speed metal. And of course classical music was always around in my parent’s house. My father always listened to everything with great attention. He was more of a good friend than a traditional father. He never tried to train me in a strict fashion. We went on long walks and spoke about music and lots more. That left a deep impression on me – which is not to say that I ever received lessons from my father.

What awoke your interest in African music?

One of my father’s students in Hamburg was the composer Roberto Sierra from Puerto Rico, who familiarised him with salsa music. He then occupied himself with Puerto Rican and Cuban music, from which his interest in African music arose in the middle of the 1980s. He listened to many tapes of African music that I also found really interesting. That was an important influence. Another stronger influence was actually a lecture by Gerhard Kunik, an important ethnomusicologist for African music, at the University in Vienna which I found totally electrifying. That was what really sparked my interest in African music.

Africa is where your interests met with those of your father …

Partly, yes. What my father found interesting about African music was polyphony. That fascinated me too, but also other aspects such as African pop music where traces of this polyphony can be found, for example in the guitar playing. My father didn’t really get on with that.

African music has had a profound effect on your work …

My first time in Africa was in 1994 (on the Ivory Coast as part of a project with the Goethe Institut) and I’ve been travelling there several times a year ever since. I’ve had a second home in Johannesburg for several years, and my long-term partner comes from there, which has

strengthened my connection to Africa even more. I collect information, listen to musicians and initiate experimental music projects with African musicians.

Musically speaking, you have followed your own path. Does your father nevertheless have an influence on your compositions?

In the last few years I have composed a lot of pieces where his influence has become more evident. This wasn’t a conscious decision, and I only realised this in retrospect. In the last four years I have worked less with electronics and concentrated on instrumental ensembles. In 2015 I wrote an almost half-hour work for solo marimba, Thinking Songs, perhaps the most difficult work in the repertoire for marimba. The marimba virtuoso Ji Hye Jung plays it fantastically, an unbelievable achievement. This piece certainly has a connection to my father’s piano etudes, particularly in the way technical problems and complex counterpoint are used as a way of creating a conceptually new kind of music. Two of my works for chamber orchestra, Surroundedness (2012) and Curtain (2015) contain elements of my father’s micropolyphony, although I apply the technique in a quite different way. In Surroundedness there is also the imitation of electronic sounds through purely instrumental means, something which my father was also concerned with. Also worth mentioning is That Which Has Remained … That Which Will Emerge, a ‘performed sound installation’ with electronics and improvisation that I created as artist-in-residence at the Polish Jewish History Museum in Warsaw and performed together with Warsaw musicians. That was for me the first opportunity to musically process my own Jewish ancestry (although not necessarily from Poland). The piece will also be released this year on CD.

How are you continuing your work with African music?

In 2016 I composed a Suite for Burkina Electric and Symphony Orchestra; that is, a piece for orchestra and an electronic pop band from Africa, in which I also perform. That was a commission from the MDR Symphony Orchestra in Leipzig; this was quite a challenge but also a lot of fun, and I was very satisfied with the result. Such a piece poses complicated methodological questions. For example: an orchestra plays with sheet music, whilst an African pop band does not. How can these different approaches be brought together? I find these questions fascinating. This project doesn’t have so much to do with my father, apart from an appetite for musical-conceptual adventure. But in the end, that’s the most important thing!

translation: Samuel Johnstone