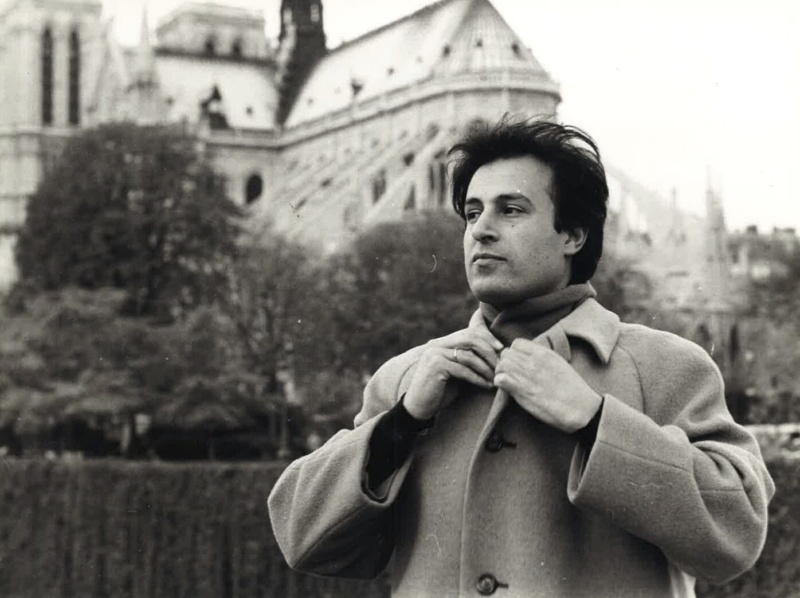

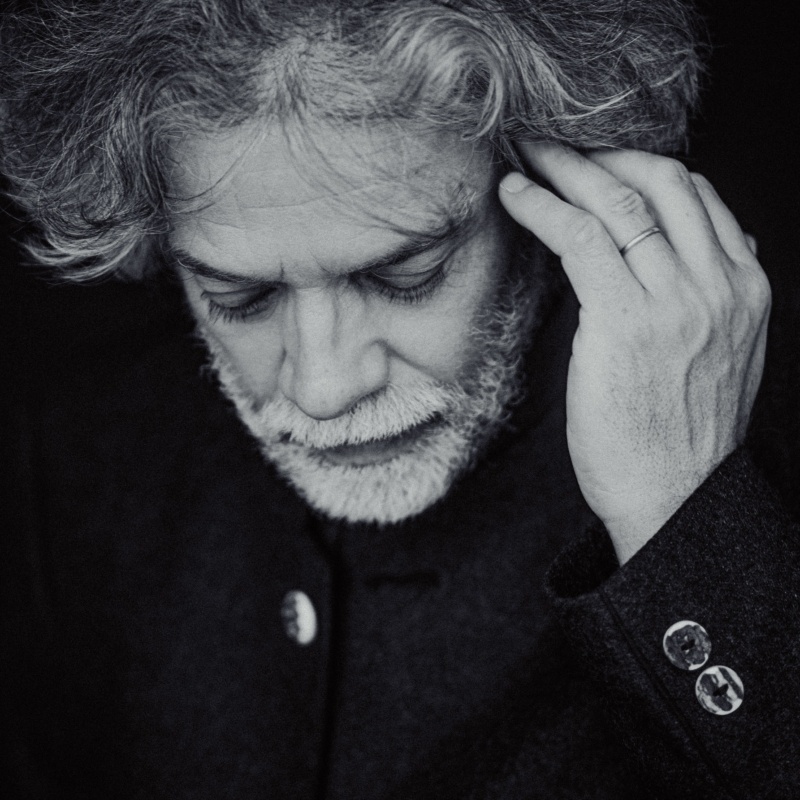

The Argentinian conductor will make his debut at the Salzburg Festival in August with the Mozarteumorchester in concert performances of Massenet’s Werther. In the run-up to the festival, Alejo Pérez talked about the interaction between directors and conductors in opera productions, his love of language and literature, and magical moments on-stage.

Mr. Pérez, it is no secret that you are a big Mozart fan. Your debut in Salzburg will unfortunately be with Massenet…

AP: Not unfortunately (laughs). It’s true that I love Mozart with all my heart and that the invitation to come to Salzburg was a happy surprise. But I also feel very at home with French repertoire, which is why I am looking forward to conducting Werther with the Mozarteumorchester.

Is it true that your connection to the Salzburg Festival was established through the former artistic director Gérard Mortier?

I can only assume that. Gérard was always an extremely discreet man and never spoke of such suggestions on his part. But I can well imagine that this was the case. I liked Gérard a lot and he was always very generous to me.

You have regularly conducted at the Teatro Real Madrid since the 2010/11 season. This collaboration during Gérard Mortier’s tenure hinted at much more than a normal guest contract.

That was a system that Gérard Mortier favoured: there was a strong group of four or five regular conductors with whom he planned the seasons. He didn’t look for specialists in particular eras and styles but always looked for people who, in his eyes, had a command of all the relevant areas. He became a confidant for this small group of artists, very friendly and full of respect. The collaboration was ongoing; we planned three or four seasons in advance. I went to the theatre up to four times a year and was also on the panel at auditions. In this way I developed a permanent relationship with the orchestra, with the choir, with the whole house. It was a very special period for me.

After Gérard Mortier’s death in 2014 your relationship with Madrid did not end, however.

No, I have since been involved in projects that were not planned by Mortier.

As musical director of the Teatro Argentino in La Plata, where you pulled the artistic strings from 2009 to 2012 and conducted great works of the opera and concert repertoire, you were able to witness the productions first hand (in Madrid too, to a certain extent). Is it possible to get so close to a production as a normal guest conductor?

Only if you are in contact with the director from a very early stage. For me it’s ideal to meet him as soon as he starts developing his concept – if indeed he is open to that. Then right at the beginning of the staging rehearsal, and of course later as often as possible. It’s definitely crucial to not come in just at the end, as is unfortunately often the case in the opera world.

During the initial stages of a production, do you simply read up on the director’s concept or do you give your own input?

It’s always different. The exciting thing is that the action is contained in the music; a lot about the psychology of the characters is apparent in the music. It is difficult if the staging involves lots of conflicting meanings and the director claims that there is a different meaning behind the words that the singer sings. Sometimes this difference is simply not there in the music and that can lead to conflicts. Of course, I always do my best to make sure the production works well as a unity, not just on the musical side. In this respect I do intervene – respectfully, but most of all with respect for the work.

Alongside directors who enjoy this, there are doubtless some who are not so open to this kind of team work…

In my opinion, one can say anything one likes; you just have to choose your words more carefully. As long as my counterpart understands that I’m looking for the best for the work and not just for me, it’s not a problem. But it really depends and I have to admit that there are conflicts between directors and conductors – it’s even typical. You have to understand the director’s set of problems: during the performances they can’t change or influence anything anymore. Everything is then in the hands of the artists on-stage, the conductor in the orchestra pit and the director can only observe. It’s a difficult role.

Coincidentally, Peter Konwitschny’s staging of Rihm’s opera Die Eroberung von Mexiko will be running in Salzburg while you are rehearsing there. You will take over conducting this production next year in Cologne.

I already conducted the piece in a different staging at the Teatro Real

and it’s very useful to see the production in Salzburg now and make

inquiries: how was this or that problem solved? There really are a lot

of difficulties in the piece, for which there is not necessarily one

single solution.

Before that, you are involved in another

large work: in December you will conduct Parsifal in your native

Argentina at the Teatro Colón.

It was originally going to be staged by Katharina Wagner but in the interim the theatre direction changed and the new artistic director went for a different production. I have already worked on many operas with Marcelo Lombardero, who will now stage Parsifal. Naturally for me it’s exciting to be conducting Parsifal at the Colón.

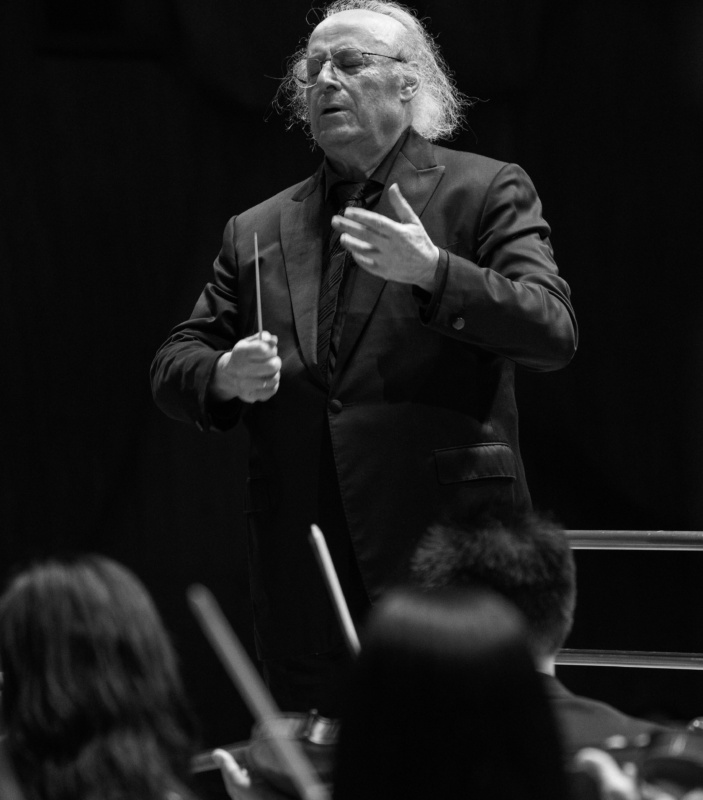

Alongside the many operas, you have also conducted orchestral concerts with a range of renowned soloists in recent years.

There have been collaborations with artists that have shaped me greatly, even if it was just for one concert. Meeting Martha Argerich was a very special experience, so too was meeting Mischa Maisky. These were encounters with great musicians who have enormous expressiveness when they perform, and who also have very warm personalities.

It is probably very relaxing to be able to concentrate wholly on the music during concerts without the necessary communicative trimmings that come hand in hand with opera productions?

Of course. I love both. Although in opera you can also experience real magic. Sometimes it works better with some directors than with others – but, together with the singers and musicians, I definitely enjoy this feeling of ‘this evening it’s going to be different, without fail’. Sometimes the stars are aligned correctly and then it just happens: everyone listening together, picking up on every nuance as if playing chamber music rather than a four hour-long opera. There is a certain element of freedom involved, you breathe differently every evening. It is exciting to sense these subtleties and the enthusiasm of the many artists who are on-stage in front of you, and to react to this. It’s what makes the job exhilarating.

You can generally communicate with the musicians and singers in their mother tongues – alongside Spanish you also speak excellent Italian, French, English and German, and you are learning Russian. Do you go the extra mile to facilitate rehearsals?

I do it for the love of languages, of literature. I believe it enriches a person and you learn nuances and subtlety. When I was younger, I read a lot and it was a dream to frequently read in the original language. If it now benefits my work then that is obviously a great thing. I try very hard to get as close to the musicians as possible and to come across as naturally as possible with the help of language.

... and your language knowledge is also no doubt very useful regarding opera repertoire. Do you currently have your heart set on any particular repertoire that you would like to conduct in the near future?

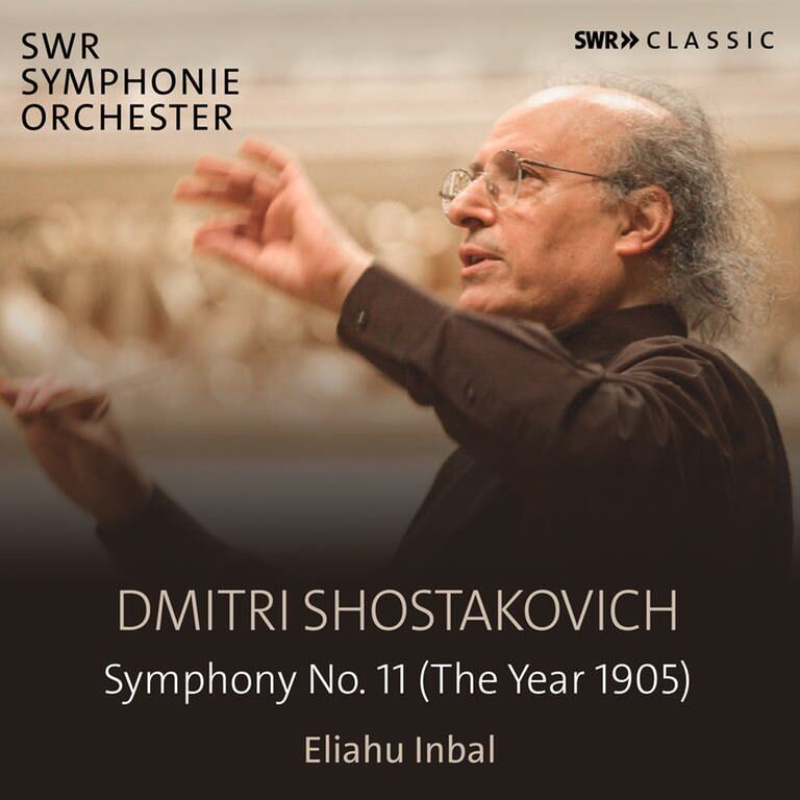

When it comes to repertoire, I haven’t left any stone uncovered so far. I would like to exhaust, extend and intensify every possibility. German repertoire has always fascinated me – Strauss, Wagner, Mahler – and then of course the 20th century: Janáček, Stravinsky, Shostakovich. But there is so much more. French music… and so on. I could go on forever about composers whose works I would like to study.

Nina Rohlfs, 07/2015 | Translation: Celia Wynne Willson