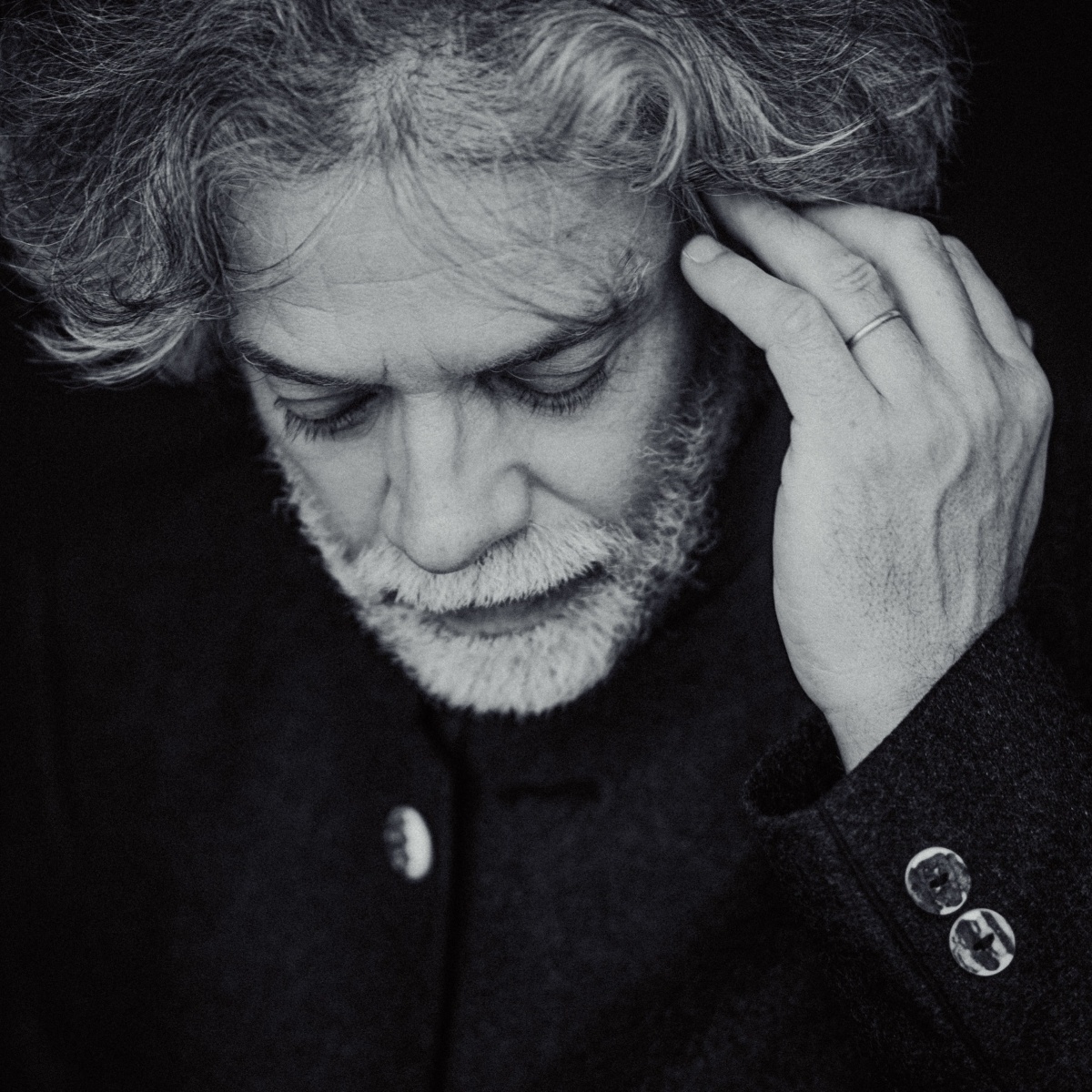

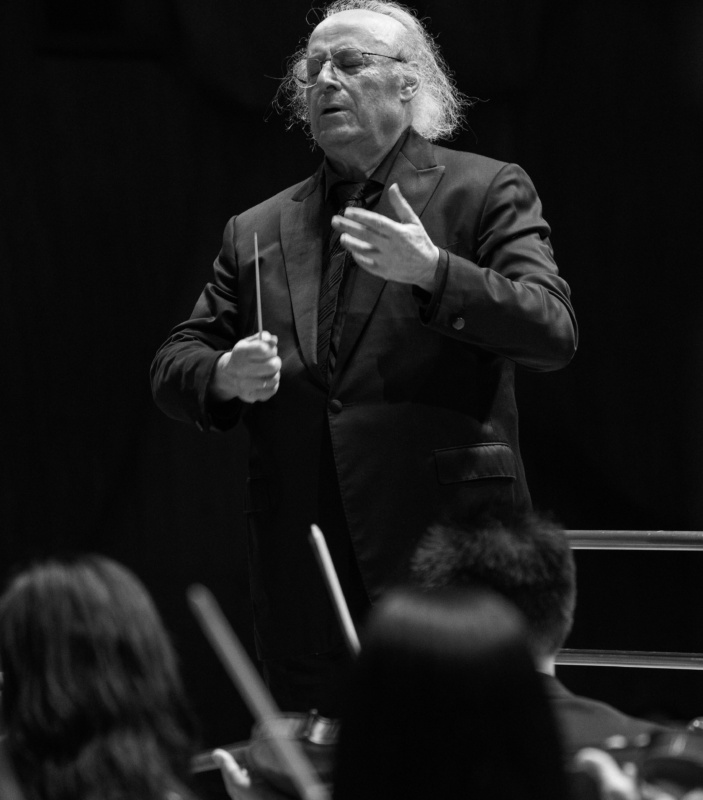

Since 2012, he has dedicated himself to this particular challenge, now taking it even further with the two piano concertos by Johannes Brahms. In an interview, the pianist described the peculiarities of his double role and his path to conducting.

What was your first experience with play/conduct, and what motivated you to get involved with it?

In 2012, I conducted from the piano for the first time, leading the Orchestre Philharmonique Royal de Liège in the Beethoven concertos – my core repertoire. This incredible adventure was attractive to me for two reasons. Firstly, I wanted to rediscover the spirit that prevailed in the times of Mozart and Beethoven, when the soloists performed on the instrument with the attitude of a chamber musician. Secondly, it helped me make a dream come true. Passionate about the orchestral repertoire, I have always considered conducting to be a natural extension of my career as a pianist. And play/ conduct is a fantastic way to move from the role of the soloist to that of the conductor. Since then, I have frequently directed Mozart and especially Beethoven from the piano; I have also recorded the Beethoven concertos again, this time with the Sinfonia Varsovia.

Conducting an orchestra while playing the solo part is not a common role. How did you learn to do it – is there a way of training or preparing?

I first worked with experienced conductors like Philippe Jordan and Pascal Rophé, who taught me a basic technique. At the same time, I watched artists who are known for their play/conduct performances, such as Murray Perahia for Mozart and Daniel Barenboim for Beethoven. I then developed my own technique. First and foremost, of course, you have to learn the orchestral part meticulously and find the most exact, unambiguous gestures so that the orchestral musicians feel supported. The piano then becomes almost a mere instrument among others. However, I must emphasize that today’s orchestral musicians perform at a very high level and with a certain degree of autonomy. At first I tried to conduct every last note, the slightest event. With increasing experience one can grant the musicians more independence and dedicate oneself to the essential.

What are the most difficult things about this role?

The main difficulty arises from the fact that soloist’s gestures are contrary to that of a conductor: the pianist’s arm moves from top to bottom towards the keyboard, while the conducting movement is in the opposite direction: from the bottom to the top. You must avoid losing the special feel of performing as a soloist, whilst constantly having to anticipate the conducting gestures in order to make the orchestra feel well led. Like a tightrope act, it is certainly associated with a certain amount of risk, but the musical result is often amazing because of its balance and coherence. The more experience I gain in all three roles – as a pianist, as a conductor/pianist and as a conductor – the more I like to switch back and forth between roles in the same concert. This is a unique and inexhaustibly rich experience.

Which play/conduct projects do you want to tackle next?

During the current season I have continued my explorations of the last great concertos of Mozart with the Concertos Nos. 22 and 23. I also conducted two Brahms concertos from the piano for the first time at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées. The big adventure of the coming season, however, will be a new play/conduct concerto which I have commissioned from the French composer Aurélien Dumont. The intention is to create a work in the spirit of the time of Mozart and Beethoven, albeit in a musical language that belongs entirely to the 21st century. The premiere will take place on 11 October 2019 at the Opéra de Limoges, and in 2020 I will perform the piece with the Orchestre de Chambre de Paris at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées.

Interview: Prune Hernaïz, 2019

Translation: Heather Hudyma