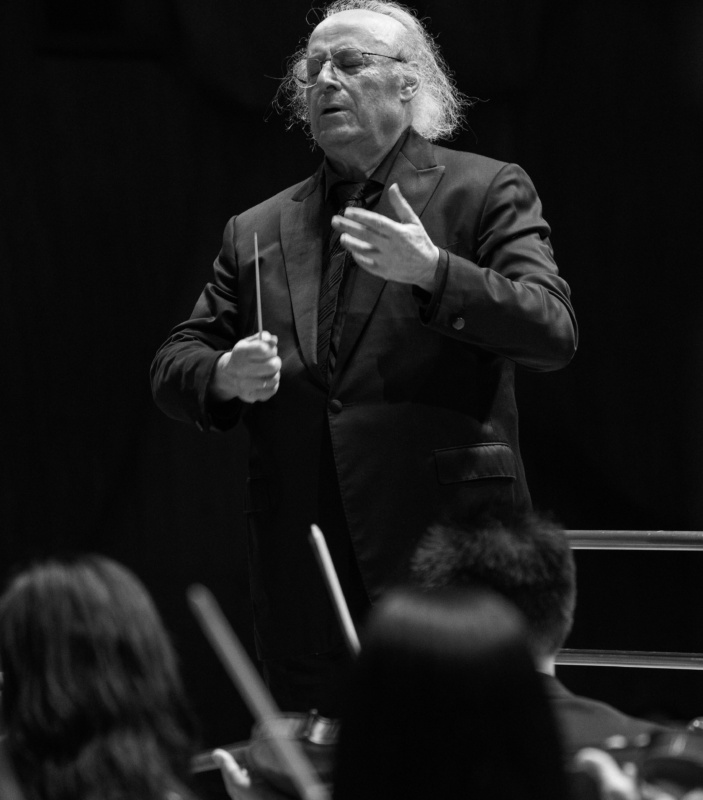

He caught the conducting bug on tour with the Ensemble Le Concert Lorrain, Nederlands Kammerkoor and Balthasar Neumann Chor. In a conversation in July 2017, Christoph Prégardien discussed his feelings about his new role, where he finds inspiration for his interpretations and to what extent life on tour is different for singers and conductors.

According to the common cliché, tenors are only interested in the sound of their own voice. You, on the other hand, are also interested in the score, and have started to conduct. How did this happen?

I never planned to become a conductor; rather, the idea slowly awoke in me. I increasingly had the feeling – especially in works that I knew very well – that some conductors didn’t take care to ensure that a performance had a singular artistic vision, especially one that encompassed the orchestra, choir and soloists. Soloists particularly are often left to their own devices, and receive little feedback regarding ornamentation, appoggiaturas or vibrato. This results in performances in which the choir and orchestra are great, but in which the soloists are almost like foreign bodies. There are a few conductors – interestingly, mostly period musicians – that care for a consistency with the soloists: René Jacobs, for example, as well as Herreweghe, Koopman and Gardiner.

Do soloists sometimes find it an imposition when someone tells them which ornamentation to use, for example?

There’s a great openness in the fields in which I’ve worked. The younger generation of singers has a different approach towards their work. This diva-ish behaviour which you associate with big names in opera is a thing of the past for the current generation. I have never had problems in telling singers to try it like this, to use a little less vibrato here, or to sing a little quieter there.

Here you surely have a lot more authority than a conductor who isn’t so familiar with the voice.

Exactly. Choirs are especially open and happy when there is someone standing up front who knows their problems well. On the other hand, I can’t work with the orchestra on a string issue as well as someone who has been there for 30 years and might also be a violinist themselves. Here I rely on the help of the principal violinist or cello continuo. But as well as working with singers, there are other things that conductors who are instrumentalists might pay less attention to, for example phrasing. Something else which is very important to me is the connection between words and music, and the composer’s interpretation of the source material. I have great experience of this from my long career and have insights that might be new for some. In this respect I have profited from some great conductors with whom I have been able to work, for example the way in which Harnoncourt built pieces around the text rather than the musical structure. This made a great impression on me and was very informative. On another level, I felt that no-one understood Bach quite so well and was so close to the text as Philippe Herreweghe. He can get so much from the baroque language, especially on a spiritual level. This subtext is very important, especially in spiritual music.

Could you perhaps take a half-step back and briefly describe how you came to conduct for the first time?

In the context of my dissatisfaction with certain performances, I was speaking to Stephan Schultz, artistic director of Le Concert Lorrain, and mentioned that I had a desire to conduct. Then we planned the St. John Passion for 2012. I had always sung the part of the Evangelist from the full score, not the piano reduction, and so thought that I already knew the score fairly well. But when I began to prepare, I realised just how complex such a score is. I read lots of secondary literature and took conducting lessons and met with Marcus Creed, who had a wonderful assistant who I still meet when problems arise. I also got in touch with Fabio Luisi: “Fabio, I will be conducting for the first time in 2012, would you give me a couple of lessons?” He said: “I’ll show you how conducting works if you explain to me a little about Bach.” When he conducts, his body, hands and head act as one, regardless of whether the music is from the 20th, 19th or 18th century, which is exactly what I am aiming for. I wanted to confound the expectation that I wouldn’t be able to pull it off since I’m a singer, and so prepared very intensively for my first appearance.

You have now been on tour several times as a conductor. Life on the road as a conductor must be quite different, since as a singer you have to protect your voice whilst as a conductor you have to speak a lot before the orchestra.

What is very interesting is the energy level. As a singer you always need to make sure that you save yourself for the evening of the concert, and therefore try to relax on the day of the concert. When you have a large part to sing, such as the Evangelist in the St. Matthew Passion, you also try not to over-exert yourself in rehearsal in the days leading up to the performance. In contrast, as a conductor you are the first to arrive and last to leave. However, this doesn’t affect you; you still have so much energy. I’m not sure whether that is because of the responsibility, or because it is just so much fun. What is also interesting is that the pre-concert nerves are totally different: when I go on-stage as a singer, I am extremely nervous half an hour before – that is actually still the case. As a conductor it was also bad the first time. I thought, “You have to go out now, give the upbeat and be present for the whole piece.” But it was such fun that an energy came to me I couldn’t have foreseen, and before my second appearance I was totally not nervous anymore. And do you know what the best part of it is? As a singer, one is used to looking at the audience. Whilst one often sees nice things, sometimes one dwells on how they are behaving or reacting. But as soon as you turn around as a conductor, you see 30, 40, 50 musicians before you, all looking at you with bright and expectant eyes.

You have also done both simultaneously – sung and conducted.

Yes, both the St. Matthew and St. John Passions. On my first tour I actually wanted to just focus on conducting, but of course I received requests to also sing the Evangelist, which I repeatedly turned down until a performance in Lucerne. That was the twelfth concert out of thirteen, and there I said to myself: “You can do it”. It was somewhat difficult in terms of choreography, as I had already conducted eleven times in a normal configuration and didn’t want to change everything around. However, it went very well and was a tremendous success, and we did the St. Matthew Passion there the same way two years later. I must say, when you are not just the conductor but also get to sing the Evangelist; that really is the icing on the cake – albeit very demanding!

You will conduct Mozart for the first time in 2019 with the Duisburg Philharmonic as well as the three great Bach works. Do you have to upgrade or rethink your conducting technique for this?

I think it is a similar procedure on another level. Naturally, a work such as Mozart’s Requiem is constructed differently than the St. Matthew Passion, for example. There are longer movements, a different style and an orchestra used to a “normal” conductor. I will of course have to adjust myself a bit. In early music circles the conductor is on the same level as the musicians, but with a symphony orchestra one has another authority. But I think I’ll get along just fine as I have ample experience with such orchestras, especially with the Duisburg Philharmonic, with whom I have sung a lot as a soloist. I am particularly excited for the first part of the programme, in which I’ll perform concert arias by Mozart together with my son Julian and niece Julia Kleiter. There are lots of extended recitative sections which are very demanding for the conductor.

Apart from your upcoming performances do you have any other pieces that you would like to conduct, perhaps also “pure” orchestral works?

Nothing of the sort has been planned yet; I have a great respect for structuring a symphonic movement so that it makes sense musically. The structure of a phrase in vocal music is often self-evident, since one has the text as a basis. In a pure orchestral piece one doesn’t have this, and in a classical symphonic movement one has to create a musical arc that stretches for 15 or 20 minutes. I would love to do this when the opportunity arises, but not quite yet. Firstly I will lead an a cappella programme with the Netherlands Bach Society in 2019, with Schütz’s St. John Passion and motets by Bach and Mendelssohn. Another great experience in May was a big celebration concert for Philippe Herreweghe’s 70th birthday, featuring many of his friends from the music world, in which I had the chance to conduct the Collegium Vocale for the first time – an ensemble with whom I have sung many concerts. That was very emotional for me. At the end there was a birthday serenade for all the musicians written by a Belgian composer, which I also conducted. The whole thing led to a possible invitation to lead the Collegium Vocale on tour in the Christmas Oratorio in 2020. To be able to lead Philippe’s ensemble and orchestra on tour would be wonderful. Regarding wishes, there are two pieces that I would really like to conduct. One would be Mendelssohn’s Elijah, and the other Hans Zender’s “composed interpretation” of Winterreise with my son Julian, which I have also often sung. When I look through the repertoire there are quite a few things that I can imagine doing.

Nina Rohlfs, 8/2017. Translation, Sam Johnstone